Exploring the Uniformity of South Carolina Teacher Vacancies

Analyses were conducted on teacher vacancies at the start of the 2020-21 school year in SC school districts using data from the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement (CERRA) and district demographic information from public data files prepared by the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE). Results of these analyses provide a descriptive profile of the teacher vacancies from these data sets. An analysis was also conducted to examine the relationship between teacher vacancy rates and student achievement using data from SC’s School Report Cards.

Takes One to Know One: How Empathy Made Me a Better Teacher

Have you ever had that dream that you were falling and couldn’t stop? That you had no control over what was coming next, and all you could do was hope for the best? I have. I’ve experienced this very sensation – while awake in a classroom.

In the summer of 2019, about 40 educators, including myself, gathered to map out strategies for student support and engagement for the 2019-2020 school year. To be one in the room was truly an honor for me. I was an instructional aide who had managed classes independently for four years. Yet, I sat there ignorant and afraid. I felt small in this incredibly large classroom of experienced educators.

In this room breathed hundreds of years of combined experience. In this room, fast-paced conversation spanning learning objectives and assessments (or alphabet soup to me) flew easily among colleagues. They may as well have been speaking a foreign language. I was mortified. I was afraid to ask questions for fear of using the wrong words and embarrassing myself in front of my peers. I was afraid to confirm what I assumed everyone in the room was already thinking: that I didn’t belong there. I wanted so much to be there. As independent as I had become, I was still aware of how indecision, anxiety, and fear plagued my twenties. A career path had seemed elusive until now. Here, I had finally found a place where I enjoyed working 40 hours a week – or so I thought. In that space on that warm June morning, I was no longer sure I had what it took to take on such meaningful, important work.

Like so many paraprofessionals, I had to decide: would I continue on my path as an instructional assistant, or would I work to earn a teaching certificate?

Like so many paraprofessionals, I had to decide: would I continue on my path as an instructional assistant, or would I work to earn a teaching certificate?

God knows I would welcome an increase in pay! But enrolling in a second Master’s program in my late thirties with a husband at home and two children to raise was a risk I had never imagined I’d be taking. How would we ever recover from all the student loan debt? What if I failed? Did I truly have what it takes to be a real teacher? Who would grocery shop, cook dinner, and make sure the girls had matching socks? I was overwhelmed with anxiety about the effect my decision could have on my family. But I was grieved at the thought of facing a future full of regret. In the end, my passion for learning got the better of me, and I’m so glad it did.

In the spring of 2020 – in the midst of a global pandemic no less – I took the leap and enrolled in an online Master’s program. Through a district partnership, I was afforded the opportunity to move toward certification, even with my busy schedule. I am in my tenth course right now – the home stretch.

I can feel my confidence growing as I learn the language of pedagogy. Now, I am self-assessing almost obsessively, mentally tracking data daily as I take account of every teaching success and failure throughout the workday. Opportunities abound thanks to my administrators’ belief that a job title has no bearing on an individual’s potential.

Because North Springs Elementary is a PDS school, our school community has access to anti-racist curricula and culturally relevant resources. This is significant, as something as simple as seeing one’s own culture represented in a storybook can build children’s confidence in ways some people can only imagine. It can be challenging for students of color to find motivation to read if they cannot relate to the stories being told. Research shows that picture books can prompt meaningful conversations about real-life situations. Our diverse population of students is able to relate to content because our educators are being trained to make the curriculum culturally relevant. Through professional development, personal storytelling, community building, and investment in resources, the Center for Educational Partnerships at UofSC is positively influencing a new generation of scholars who will enjoy learning because they can see how knowledge can impact their lives. They can see the big picture – and they’re in it!

In years past, I saw my age and excessive job history as cringeworthy. Now, I celebrate that seemingly haphazard past. My vulnerabilities have fostered in me an empathy for the child who seeks to understand but instead finds a struggle. I know that struggle. I also know there is something beautiful waiting on the other side of that struggle.

My vulnerabilities have fostered in me an empathy for the child who seeks to understand but instead finds a struggle. I know that struggle. I also know there is something beautiful waiting on the other side of that struggle.

As an educator, it is my responsibility to guide my students to the other side, encouraging them to value their own voices and talents as tools for the journey. I feel connected to students in a more meaningful way. I’ve been exactly where they are. I have sat in a room full of people and felt like everyone was singing a song I had never heard before. I have politely clapped along, hoping no one would notice. I now recognize that trepidation in my students. I am equipped to help them catch the rhythm of learning because I myself am catching the beat. The only differences between us are time and opportunity, two things there are plenty of when educators become advocates for their students.

This is the privilege and honor of teaching.

This story is published as part of a storytelling retreat hosted by the Center for Educational Partnerships (CEP) housed in the University of South Carolina’s College of Education. CEP partners nominated practicing educators, administrators, and system leaders to share their stories. The Center for Teaching Quality, a CEP partner, facilitated the retreat and provided editorial and publication support. Learn more about this work and read additional stories by following @CEP_UofSC and @teachingquality.

Retaining Teachers through Talent Centered Education Leadership

ABSTRACT

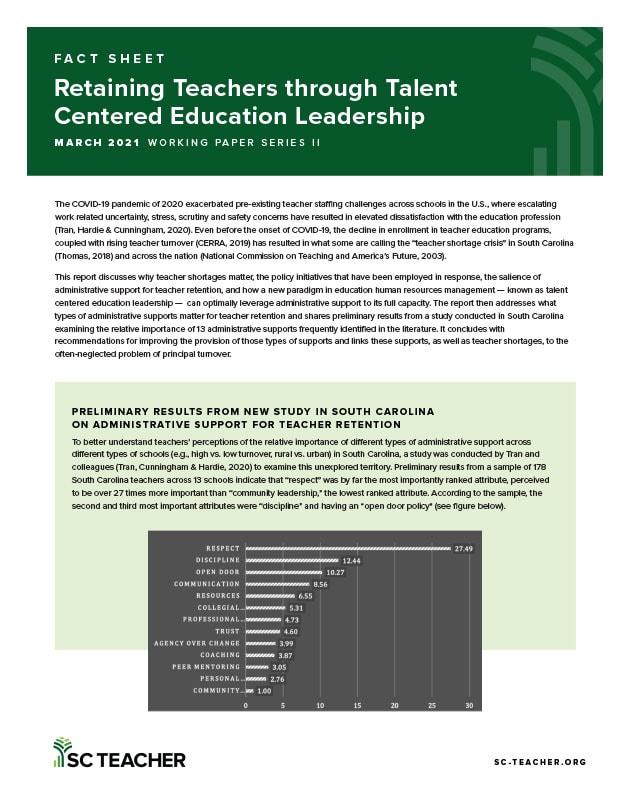

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 exacerbated pre-existing teacher staffing challenges across schools in the U.S., where escalating work-related uncertainty, stress, scrutiny, and safety concerns have resulted in elevated dissatisfaction with the education profession (Tran, Hardie & Cunningham, 2020). Even before the onset of COVID-19, the decline in enrollment in teacher education programs coupled with rising teacher turnover (CERRA, 2019) have resulted in what some are calling the “teacher shortage crisis” in South Carolina (Thomas, 2018) and across the nation (National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, 2003). This report discusses why teacher shortages matter, the policy initiatives that have been employed in response, the salience of administrative support for teacher retention, and how a new paradigm in education human resources management – known as Talent Centered Education Leadership (TCEL) – can optimally leverage administrative support to its full capacity. The report then addresses what types of administrative supports matter for teacher retention and shares preliminary results from a study examining the relative importance of 13 administrative supports frequently identified in the literature. The paper concludes with recommendations for improving the provision of those types of supports; it also links the supports, as well as teacher shortages, to the often-neglected problem of principal turnover.

Why I'm Still Here: Reflections on the Choice to Teach

"Remember that you chose to teach middle schoolers."

Gabe, one of my students from student teaching, couldn’t have known how this small note would have me laughing, then sobbing, all sniffling nose and leaky tears, one year later. This was the sentiment he chose to leave with me at the end of my student teaching, back when I had the glow of someone who was not solely responsible for report card grades, parent contacts, and certification requirements. Back when I prayed daily for my future students, when I got teary-eyed thinking about how they were already out there--my students, just waiting on me.

I chose them with first-year fire, and here’s the painful lesson I learned: they don’t always choose you back.

Countless reflections on my teaching philosophy and in-class movies of life-changing teachers primed my heart to expect everything I had dreamed of and more. Sure, lesson plans would be demanding. After-school duties would certainly kill my feet. I might not drive out of the parking lot until seven o’clock most days. But it would all be worth it because of the hours I got to spend teaching.

I was mentally preparing scrapbook pages for the montages of amazing moments to come. And some of my first year would end up fitting right in: learning about argument by writing to local legislators who then wrote us back; holding a courtroom case for characters from Rikki-tikki-tavi; coaching a powderpuff team; taking selfies during spirit week.

However, much of my year wouldn’t have made the cut. A collection of well-written-yet-disastrous lessons, discipline notes, and classroom management drafts seemed much more fit for the shredder than anything paste-worthy. I made a million mistakes; crying in my car became a regular routine. With tears in my eyes, I told myself that my students deserved a better teacher. That maybe the year wouldn’t have been such a mess if someone else had been hired in my place.

So why am I still here?

Reclaiming my first year took sitting in the middle of all my mess and deciding this: there was still something solid to cling to--the very thing that I thought I had failed so miserably at--my choices.

First year teacher, there is as much room to grow as there is to fail, and most of the time, they’re not mutually exclusive. I began the year with starry-eyed classroom “rules” that were so vague, they belonged on an inspirational poster instead. (“Work until you’re proud?” Why should they want to work? What does it mean to be proud? Exactly how many pages does she want?) These “rules” did nothing to drive engagement and expectations in my room.

In the midst of my mid-semester crisis, I turned to my CarolinaTIP coach, from the University of South Carolina’s College of Education, whose advice became the catalyst for reclaiming the year. The year began to pivot when we sat down over Winter Break and I got a crash course in rules versus expectations. With my coach’s guidance, I created a revitalized management plan that set clear expectations, established rules with equitable consequences, and gave us all the structure we needed to breathe and focus on learning.

I greeted students in January as if it was the first week of school. They received a new syllabus, and we practiced for two weeks how to sharpen our pencils, when to raise our hands, where to get materials, and what felt like a hundred other things until our classroom machine became a bit more oiled. We laughed more, relaxed our shoulders, and spent more time excited about reading.

Of course, with all of the improvements in learning that this led to, it wasn’t a fix-all solution. For some students, it was going to take them showing up for eighth grade the next year and still seeing my name on a tag in the hallway to hear the mantra I was repeating over and over to my heart: I refuse to give up on you.

Now with my third year of teaching behind me, I have something more to say: I refuse to give up on myself. I am here for a reason. I can only get better at loving them. They will look back one day and see how much I cared.

They are so important. There is more to them than drama and social media and one-week relationships. We need each other. Do not underestimate their spirits or potential.

If you’re feeling helpless, hopeless, or homeless, know that you have not failed. Your first year doesn’t have to look like a made-for-television event to prove you can be a great teacher (neither does your second or your third or your fourth). You are making an impact now, and that impact will expand and grow as you teach and teach and teach.

Please, keep choosing your students.

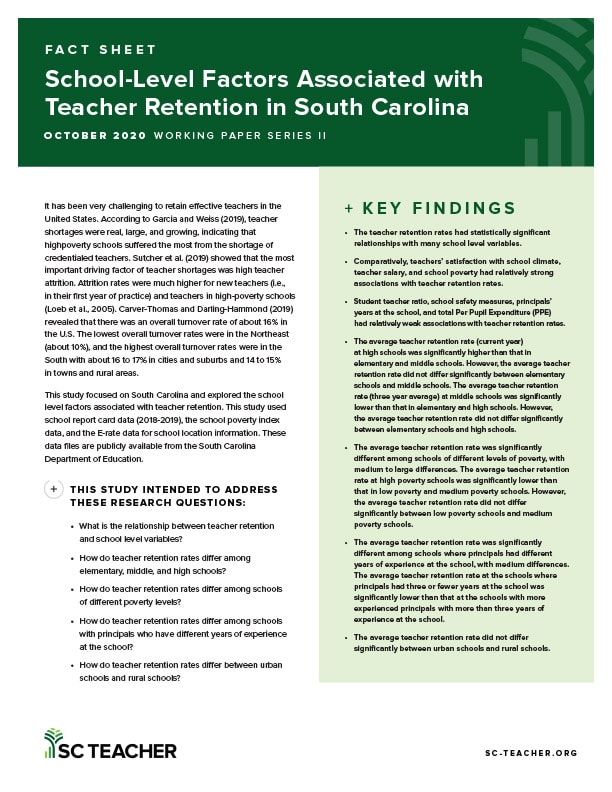

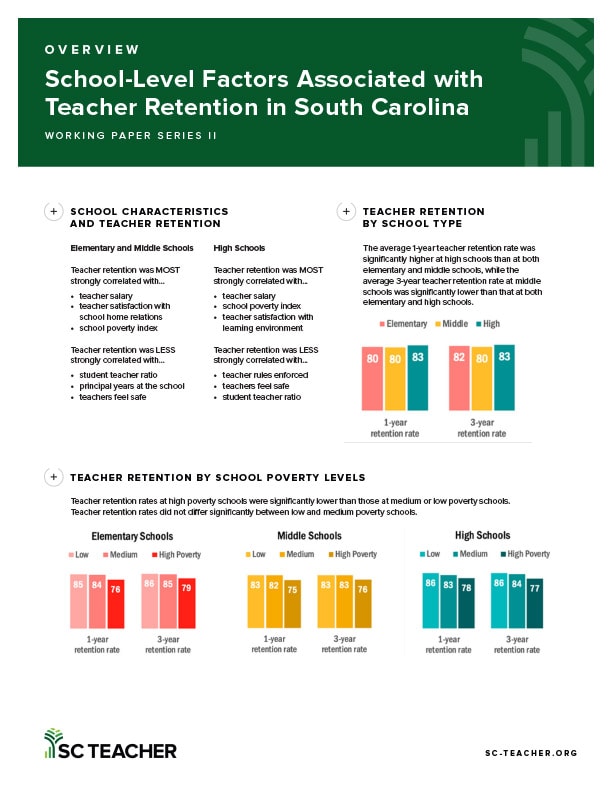

School-Level Factors Associated with Teacher Retention in South Carolina

ABSTRACT

Retaining teachers is an ongoing challenge in K-12 education in the United States. Teacher turnover rates in the South, including South Carolina, are even more pronounced. To gain an understanding of the overall conditions regarding teacher turnover in South Carolina, we investigated school-level factors associated with teacher retention in the state. An analysis of 1,100 public schools in 82 school districts revealed that teachers’ satisfaction with school climate, teachers’ views of school safety and student behavior, school poverty, principals’ years at the school, and teacher salary played important roles in teacher retention. Additionally, the average teacher retention rate at high schools was significantly higher than that in elementary and middle schools. Further, the average retention rate at high poverty schools was significantly lower than that in low and medium poverty schools. Moreover, schools with new principals (three or fewer years of experience) had significantly lower teacher retention rates than the schools with experienced principals (more than three years). Finally, teacher retention rates did not differ significantly between urban and rural schools. We conclude this paper with recommendations and suggestions for strategies to retain teachers in South Carolina.

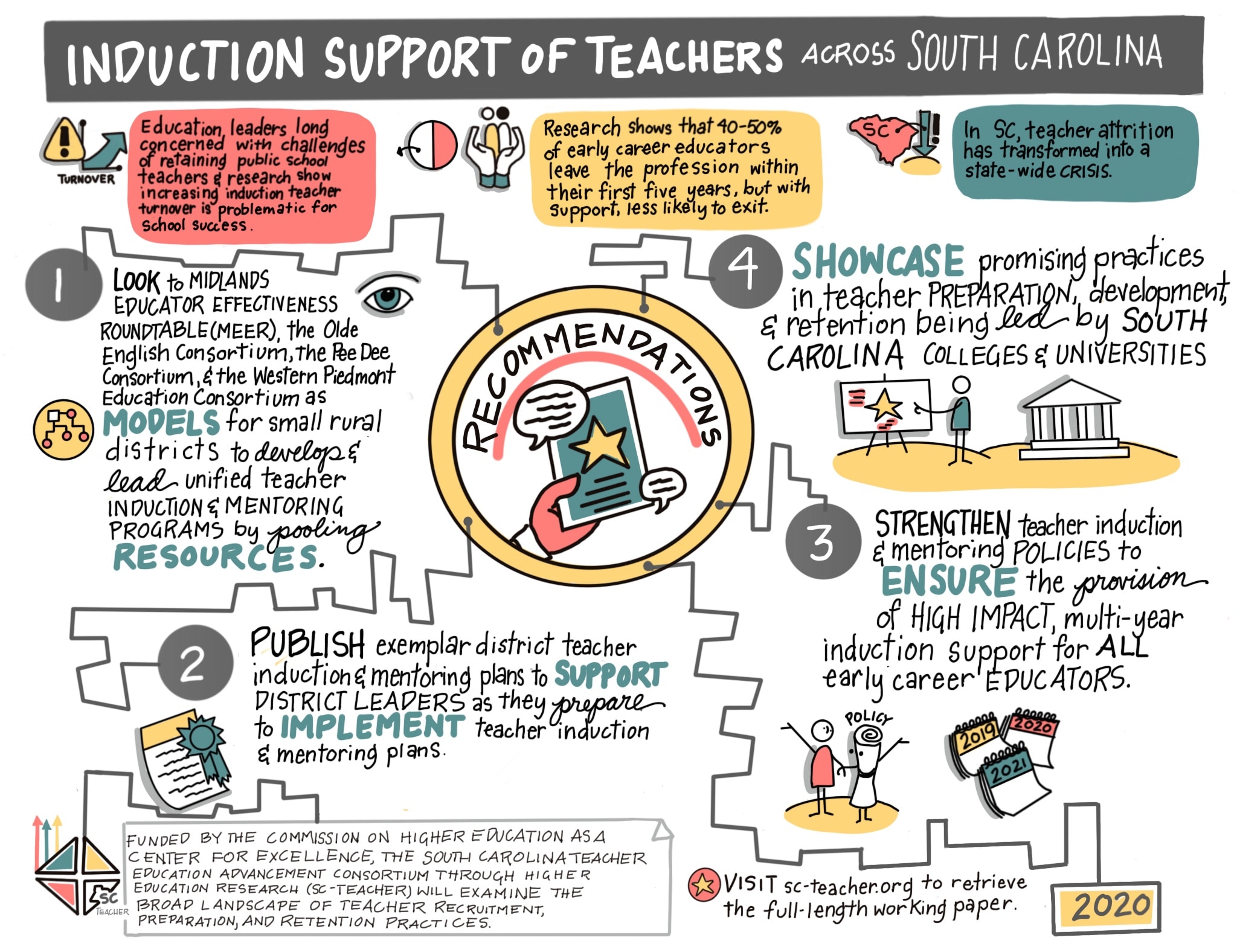

Induction Support of Teachers Across South Carolina

ABSTRACT

Our nation continues to experience challenges with K-12 teacher shortages. The same is true for South Carolina. Teacher shortages in South Carolina primarily result from teacher attrition which has transformed from a problem to a state-wide crisis over the last decade. Between 40 and 50 percent of early career educators leave the profession within their first five years, which emphasizes the critical point of intervention for teacher retention during this early career stage. Teachers who receive early career support as they transition into the profession are less likely to exit the profession early. In this paper, I discuss the challenges associated with teacher attrition and the need for induction support, review promising practices of induction support programs In South Carolina, and share conclusions and recommendations.

Supporting Novice Teachers in the Time of COVID-19

Last June, my four-year-old asked me when Christmas would be here. I answered, “Six months.” “Six months is FOREVER!” was his response. I immediately started going through the mental list of things to do with two small children and a large extended family and thought, “Six months is not nearly long enough!” This difference in perspective is something we expect between adults and small children. For my son, six months is an eighth of his life; for me it’s a tiny percentage. We discuss this phenomenon in the Carolina Teacher Induction Program (CarolinaTIP) where I work as a coach for first, second, and third-year teachers. As a “grizzled” 20-year classroom veteran, I know there will always be new students, new parents, new administrators, new standards, a new school initiative, a new day. I’ve seen it happen over and over. So, I can handle an unfamiliar online gradebook or a schedule change fairly easily. When it comes to classroom experience, I am reminded that novice teachers have much less context and that the things happening take up a far bigger “slice” of memories. While I can move past a negative parent email knowing it represents a tiny fraction of all emails for the year, that same email may make up a full quarter of all the parent communication a young teacher has ever received. A CarolinaTIP coach lends perspective to those situations. We call it “right-sizing.” Right-sizing consists of listening to new teachers, then saying “This is normal. This is okay. I will help you navigate this,” or “This is not normal. This is not okay. I will help you navigate this.” It’s an important part of our job, and it’s our privilege to be able to support educators in this way. Whether the situation is run of the mill or catastrophic, the common denominator is the sentence, “I will help you navigate this.”

Last June, my four-year-old asked me when Christmas would be here. I answered, “Six months.” “Six months is FOREVER!” was his response. I immediately started going through the mental list of things to do with two small children and a large extended family and thought, “Six months is not nearly long enough!” This difference in perspective is something we expect between adults and small children. For my son, six months is an eighth of his life; for me it’s a tiny percentage. We discuss this phenomenon in the Carolina Teacher Induction Program (CarolinaTIP) where I work as a coach for first, second, and third-year teachers. As a “grizzled” 20-year classroom veteran, I know there will always be new students, new parents, new administrators, new standards, a new school initiative, a new day. I’ve seen it happen over and over. So, I can handle an unfamiliar online gradebook or a schedule change fairly easily. When it comes to classroom experience, I am reminded that novice teachers have much less context and that the things happening take up a far bigger “slice” of memories. While I can move past a negative parent email knowing it represents a tiny fraction of all emails for the year, that same email may make up a full quarter of all the parent communication a young teacher has ever received. A CarolinaTIP coach lends perspective to those situations. We call it “right-sizing.” Right-sizing consists of listening to new teachers, then saying “This is normal. This is okay. I will help you navigate this,” or “This is not normal. This is not okay. I will help you navigate this.” It’s an important part of our job, and it’s our privilege to be able to support educators in this way. Whether the situation is run of the mill or catastrophic, the common denominator is the sentence, “I will help you navigate this.”

Keeping this in mind, let’s consider the COVID-19 pandemic. Public schools have been closed for six weeks, and this school year will end without any P-12 students getting to say goodbye to their teachers or without their teachers getting to say goodbye to them face-to-face. Now, try to look at this semester through the lens of novice teachers who may have been just starting to get their legs under them. For some, the spring concert was going to feel slightly less intimidating because of the winter concert’s success. The upcoming third round of parent conferences might not have seemed so daunting because of the two before. Now, these educators have become virtual teachers trying to make connections and increase student knowledge in an eLearning environment. All during a time of unprecedented national fear about getting sick, worry there won’t be any food left in the grocery stores, anxiety about the actions of our fellow citizens, and concern for the economic and health ramifications of this virus. It’s enough to make me, with my 20 years of classroom experience, want to curl up into a ball until it all passes. How much more so for our young coworkers? With the teacher shortage as it is, we can hardly afford to let any of them throw in the towel before they’ve truly gotten to experience the joy of our beloved profession.

"While the COVID-19 pandemic is unique, there is enough tangential intersection with past events for veteran educators to offer up empathy to younger, less experienced teachers."

How are they doing? In the case of my own first and second-year teacher coaches, their feelings are all over the place. Some are finding solace in the establishment of office hours. Some are wondering if their students are learning, especially the ones that have been unresponsive. Some are worrying about the students who might be taking care of younger siblings or not getting enough to eat. Some are proud of their successes in virtual teaching, running video conference “classes,” and making connections with their students. They are feeling creative and overwhelmed and unsure and relieved. The common theme through all my conversations with them in the past weeks is that they miss their students terribly and are grieving that loss. I know listening is my most important job as a coach, especially with a new teacher who is grieving. When the talking is finished, and I’m left with the choice to say, “This is normal. This is okay. I will help you navigate this,” or “This is not normal. This is not okay. I will help you navigate this,” which one is true? The answer is both. This is not normal. We don’t know if it will be okay. And still, there’s some familiarity to it all.

Whether it’s been for a hurricane or some other weather-related catastrophe, we have seen people run to stores in panic. In the 1980s when the AIDS crisis hit, many of us wondered if toilet seats and water fountains were safe anymore. My first year of teaching was the year of the Columbine shooting, and my fourth year in the classroom was 9/11. Both events seemed to make the world shift right under our feet, and as teachers we were tasked with helping our students process their own fears and feelings about whether things would ever be “normal” again. When the housing bubble burst in 2008 and the Great Recession took hold, we had students whose parents lost jobs, who suddenly became homeless or stopped coming to school, who took on a whole new set of “adult” concerns about the economy.

While the COVID-19 pandemic is unique, there is enough tangential intersection with past events for veteran educators to offer up empathy to younger, less experienced teachers. As some are grieving, empathy may be the most powerful support we can give. Empathy is based in connection. It is feeling WITH someone, not for someone. It is connecting with someone’s feelings and requires us to connect with something in ourselves that knows that feeling. One of the most empathetic things you can say to anyone grieving, “I know a bit about how you might be feeling and I’m here.” There’s no solution-offering, no Pollyanna-ish “It’ll be fine!” and no pointing out silver linings. Just “I know a bit about how you might be feeling, and I’m here.” And we veterans DO know what it feels like to be worried and sad about world events. If we can find a way back to the emotions we felt in the days around the Sandy Hook shooting or the fall of the World Trade Center, we may be able to summon up the empathy to help support and hopefully retain these young professionals.

"Let’s draw upon our experience and show empathy by reaching out and checking in with that young colleague from down the hall or even in another school. We can all find opportunities to do the same."

Veterans and new teachers alike are struggling with finding a new normal for the rest of this school year and maybe beyond. I propose that for our novice colleagues, those feelings of worry, fear, and uncertainty loom even larger. Like a four-year-old’s interminable wait for Christmas, the school calendar feels much different for the novice. Let’s draw upon our experience and show empathy by reaching out and checking in with that young colleague from down the hall or even in another school. In the coming weeks and months, I’ll be right-sizing things for novice teachers the best I can, but truthfully I’ll mostly be listening and telling them, “I know a bit about how you might be feeling, and I’m here.” We can all find opportunities to do the same.